Oppenheimer and the Atomic Bombings of Japan: Debunking an Old Myth

How Truman’s Decision to Use Atomic Bombs Was Unjustified and Why Some Iranian Diaspora Opposition Figures Support It

If you’re looking for a captivating and thought-provoking movie to watch, I highly recommend Oppenheimer, the three-hour biopic that tells the story of the scientist who led the development of the atomic bomb. The movie is a masterpiece of cinema, with brilliant performances, stunning visuals, and superb pacing despite its long runtime.

Oppenheimer also delivers a powerful anti-nuclear message, which is especially relevant at a time when the US government is planning to spend a staggering $1.7 trillion over the next decades to build new nuclear weapons that could endanger the survival of all life on this planet.

But what makes the movie even more interesting is that it challenges the dominant narrative that has been used to justify the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for decades.

Stalin and Truman with Secretary of State James F. Byrnes and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov at the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, a few weeks before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At Potsdam, Truman told Stalin the US had developed a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.”

This narrative claims that the US had no choice but to drop the bombs on Japan, because it was the only way to end World War II and save untold numbers of American lives that would have been lost in an invasion.

The movie shows this narrative to be a myth, based on historical inaccuracies and political motives. Through dialogue, we learn that Japan was on the verge of surrendering, and their emperor only wanted to maintain his status and societal order in a post-war Japan. The point of wiping out Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not to force Japan’s surrender but to show the Soviets—and the world—that the US possessed such paradigm-shifting and world-threatening technology.

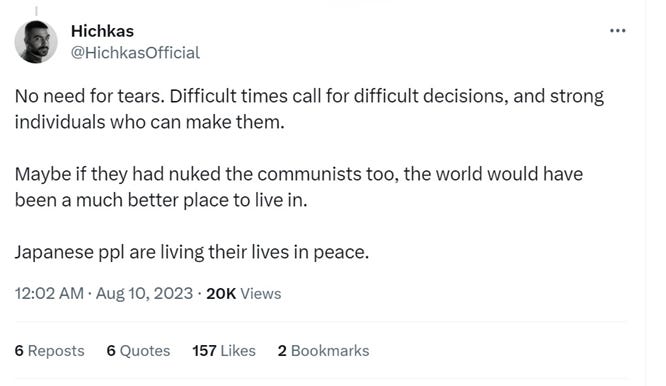

Shockingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, this historically inaccurate narrative was recently promoted in appalling fashion by controversial Iranian rapper Hichkas, who praised the US for the bombings and wished a similar fate was occurred for “communists.”

Link to Hichkas’s tweet

I suspect that Hichkas’s views are motivated by him trying to build support for foreign military intervention to overthrow the Islamic Republic, regardless of its human cost. He seems to have no confidence in grassroots-led bottom-up change in Iran.

This view, which is apparent in Hichkas’s tweets, has a marginal following among some segments of the Iranian diaspora, but it deserves thorough scrutiny. However, that is something to tackle in another post.

In this post, I want to give the historical background and facts about the US atomic bombings of Japan, and correct the ignorant and morally reprehensible views promoted by people like Hichkas.

The Historical Evidence Contradicts the Official Narrative of the Atomic Bombings

The historical evidence suggests that Japan was already on the verge of surrender before the bombings, and that the US could have ended the war sooner and more peacefully by changing their demand for unconditional surrender and accepting Japan’s request to keep their emperor.

Moreover, the historical evidence suggests that the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan had a greater impact on Japan’s decision to surrender than the atomic bombs.

Let us review some of this evidence. I have gathered this information from the superb book by prominent historian Peter Kuznick and celebrated filmmaker Oliver Stone, called “The Untold History of the United States.” I have included all the citations for the information presented below.

Japan’s Hopeless Situation and Desire to Keep the Emperor

First, it is important to contextualize the Japanese situation and mindset in 1945. Japan was facing a hopeless situation in the war. It had lost most of its overseas territories, resources, and allies. It had suffered heavy casualties and damage from conventional bombing raids by the US. It had faced naval blockades and food shortages that threatened its survival. It had witnessed the collapse of Nazi Germany, its main ally in Europe.

Japan was aware of its inevitable defeat, but it was reluctant to accept unconditional surrender, which was demanded by US President Harry Truman, because it feared that it would mean the abolition of its monarchy and the execution of its emperor, whom the Japanese population at the time essentially revered as a god.

Japan also feared a communist uprising in its own country if it prolonged the war. It was aware of the Soviet Union’s strength and ambition in Europe and Asia. It was also aware of the deal between Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin at Yalta in February 1945, which promised that the Soviet Union would join the war against Japan after Germany’s defeat.

Emperor Hirohito of Japan (reign: December 1926-January 1989)

In fact, one of Japan’s former prime ministers, Prince Fumimaro Konoe, who had served in this role three times during the Imperial era, had warned Emperor Hirohito in a memo in February 1945 that “Japan’s defeat is inevitable.” He expressed his fear of a communist revolution in Japan if they continued to fight.1

Japan hoped to avoid a Soviet invasion by negotiating a peace settlement. It was also using diplomatic channels to signal its willingness to surrender if it could keep its emperor.

The US’s Knowledge and Options to End the War without the Bomb

Many US officials knew that Japan was desperate and willing to surrender before the atomic bombings. They also knew that the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan would make the Japanese certain of their defeat. They urged Truman to alter his demand for unconditional surrender and assure Japan that they could keep their emperor.

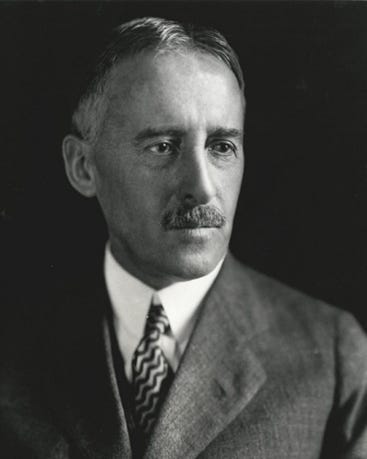

One of these officials was Henry Stimson, who had served as secretary of war under both Roosevelt and Truman. In July 1945, he sent a memo to Truman in which he advised him to alter the demand for unconditional surrender and assure Japan that they could keep their emperor.

U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson (July 1940-September 45)

Stimson wrote: “Japan is susceptible to reason in such a crisis to a much greater extent than is indicated by our current press and other current comment. Japan is not a nation composed wholly of mad fanatics of an entirely different mentality from ours.”2

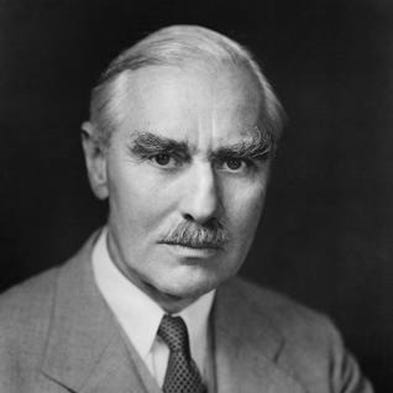

Another official who shared this view was Joseph Grew, who had served as secretary of state and ambassador to Japan. In April 1945, he wrote: “Surrender by Japan would be highly unlikely regardless of military defeat, in the absence of a public undertaking by the President that unconditional surrender would not mean the elimination of the present dynasty.”3

U.S. Secretary of State Joseph Grew (June 1945-July 1945)

Some senior politicians also pressed Truman to stop calling for unconditional surrender. One of them was Senator Homer Capehart, who stated that the White House had received an offer by Japan to surrender if Emperor Hirohito was not deposed. He asked: “What’s to be gained by continuing a war when it can be settled now on the same terms as two years from now?”4

Sen. Homer E. Capehart (R-IN, January 1945-January 1963)

Even the media questioned Truman’s demand for unconditional surrender. In June 1945, the Washington Post editorial board wrote that “unconditional surrender” was a “fatal phrase” from Truman and was proving an impediment to ending the fighting.5

Furthermore, at the time the US military and intelligence were confirming that a Soviet entry into the war would make the Japanese certain of their defeat.

On April 11, 1945, the Joint Intelligence Staff of the Joint Chiefs stated, “If at any time the USSR should enter the war, all Japanese will realize that absolute defeat is inevitable.”6

On July 6, the US military’s intelligence assessment was “an entry of the Soviet Union into the war would finally convince the Japanese of the inevitability of complete defeat.” But it added that “the Japanese believe that unconditional surrender would be the equivalent of national extinction.”7

The Motives Behind the Atomic Bombings

Truman decided to use the atomic bomb against Japan without modifying his demand for unconditional surrender or waiting for Soviet entry into the war. He believed that this would end the war quickly and decisively, and also demonstrate America’s power and prestige in the post-war world.

Truman and some of his top advisors principally saw the bomb as a tool to gain political advantage over the Soviet Union, which was America’s ally at the time but also a looming rival in the aftermath of the war. They wanted to use the bomb to intimidate the Soviets and tilt the global balance of power firmly in favor of the US by the end of the war.

One of these officials was James Byrnes, who also served as secretary of state under Truman. According to Leo Szilard and Harold Urey, who met with Byrnes in May 1945 to convince the Truman administration to not use the bomb, Byrnes knew that “using the bomb against the cities of Japan in order to win the war” was not necessary, but he was “much concerned about the spreading of Russian influence in Europe, and insisted that possessing and demonstrating the bomb would make Russia more manageable in Europe.”8

Secretary of State James F. Byrnes (January 1951-January 1955)

Byrnes also told Truman in April 1945 that the atomic bomb could put America in a position to “dictate its terms at the end of the war.”9

Another official who shared this view was Leslie Groves, who was the military head of the Manhattan Project, while Oppenheimer was its scientific head. Groves had said that the bomb was built on the basis that “Russia was the enemy” and the goal was to “subdue the Russians.”10

General Leslie Groves and J. Robert Oppenheimer, who headed the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb

The Military and Moral Opposition to the Atomic Bomb by Truman’s Top Commanders

However, some of Truman’s top military commanders were opposed to using the atomic bomb, as they considered it unnecessary and immoral.

One of them was Dwight Eisenhower, who was the supreme commander of Allied forces in Europe. He told Newsweek that it wasn’t “necessary to hit them with that awful thing” and that he “hated to see our country be the first to use such a weapon.”11

General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Another one was Douglas MacArthur, who was the supreme commander of Allied forces in the Pacific. He held a press conference on August 6, before the bomb drop on Hiroshima was announced, saying that Japan was “already beaten” and he was worried about “the possibilities of a next war with its horrors magnified 10,000 times.”12

General Douglas MacArthur

Truman’s secretary of war Stimson also opposed using the atomic bomb and said it was “diabolical” and could be the “doom of civilization.” He repeatedly tried to convince Truman to assure the Japanese about the emperor. But Truman rejected his advice and told him he could resign.13

Another voice was senior intelligence official John Foster Dulles, who later became President Dwight Eisenhower’s secretary of state. He denounced the use of the atomic bomb at the time and said that the US had set a precedent that could lead to the “sudden and final destruction of mankind.”14

Many other top US military commanders beyond Eisenhower and MacArthur also expressed their opposition to using the bomb. This even included Truman’s chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, Admiral William Leahy, who said that the atomic bombs were “violations of every Christian ethic I have ever heard and all of the known laws of war.”15

Admiral William D. Leahy

Leahy stated, “The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender…the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. In being the first to use it we adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the dark ages.”16

Truman’s Great War Crime

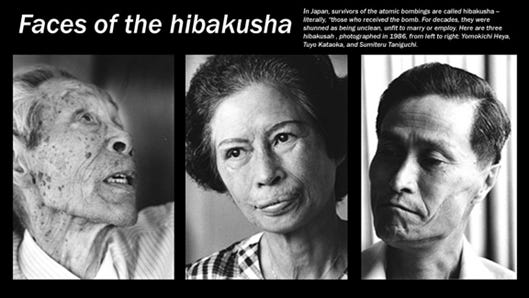

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed hundreds of thousands of civilians, inflicted horrific injuries and diseases, and left a legacy of environmental and genetic damage. Many people, including some of the US officials and leading legal experts, denounced the use of the bomb as a war crime and a gross violation of human rights.

One of them was Telford Taylor, who was the chief prosecutor of the Nuremberg trials against the Nazis. He stated “the rights and wrongs of Hiroshima are debatable, but I have never heard a plausible justification for Nagasaki.” He considered it a war crime.

Moreover, the US later accepted Japan’s core demand to keep their emperor as part of their surrender. This showed that the US could have ended the war sooner and more peacefully by modifying their demand for unconditional surrender earlier. The US ultimately did not insist on removing the emperor, but rather allowed him to remain as a symbolic figurehead under a new constitution.

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were therefore not only militarily unnecessary, but also morally indefensible. They were Truman’s great war crime.

The Soviet Invasion as the Decisive Factor for Japan’s Surrender

While the US claimed that the atomic bombings were the main reason for Japan’s surrender, many Japanese officials said otherwise. They said that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria and other Japanese-held territories in Asia on August 9, 1945 was what shocked them into immediately surrendering.

Deputy Chief of Staff General Kawabe explained, “It was only in a gradual manner that the horrible wreckage which had been made of Hiroshima became known. In comparison, the Soviet entry into the war was a great shock when it actually came.”17

In January 1946, a study by the US Department of War confirmed this. It found “little mention of the use of the atomic bomb by the US in the Japanese discussions leading up to the decision.” It added, “it is almost a certainty that the Japanese would have capitulated upon the entry of Russia into the war.”18

The Soviet invasion of Japan’s territories was therefore the decisive factor for Japan’s surrender, not the atomic bombings. The US knew this, but chose to use the bomb anyway.

A Moral and Historical Travesty

Truman’s decision to use atomic bombs against Japan was a moral and historical travesty. It was not motivated by noble intentions, but by political calculations and power ambitions. He ignored the advice of many of his top military commanders, who considered the bomb unnecessary and immoral. He disregarded the evidence that Japan was ready to surrender. He chose to use the bomb not to end the war, but to intimidate the Soviet Union and create a new US-dominated world order.

The atomic bombings of Japan had horrific effects and tragic aftermaths. They killed hundreds of thousands of people, mostly civilians, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They inflicted horrific injuries and diseases on the survivors, who suffered from radiation sickness, burns, cancers, and other ailments. They left a legacy affecting generations of people, animals, and the environment. They set a precedent for the use of nuclear weapons, which continues to threaten the survival of all life on this planet.

Hichkas’s support for Truman’s decision to use atomic bombs against Japan shows a complete lack of knowledge and compassion for the millions of people who suffered from these horrific weapons. He also shows a complete disregard for the historical facts and evidence that contradict his views. He seems to have no moral or ethical standards, no respect for human dignity, and no vision for a peaceful and just world, much less for Iran.

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and Japan’s Surrender in the Pacific War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), 37.

Henry L. Stimson, “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb,” Harper’s Magazine, February 1947, 97–107.

Hasegawa, Racing the Enemy, 52–53.

“Senator Urges Terms to Japs Be Explained,” Washington Post, July 3, 1945.

“Fatal Phrase,” Washington Post, June 11, 1945.

Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), 20.

Combined Chiefs of Staff, 643/3, “Estimate of the Enemy Situation (as of 6 July)” July 8, 1945, RG 218, Central Decimal Files, 1943–1945, CCS 381 (6/4/45), sec. 2, pt. 5.

Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb, 147.

Harry S. Truman, Memoirs of Harry S. Truman, vol. 1 (New York: Signet/New American Library, 1955), 104.

Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 284.

“Ike on Ike,” Newsweek, November 11, 1963, 107.

Dorris Clayton James, The Years of MacArthur: 1941–1945, vol. 2 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975), 774.

Henry L. Stimson, diary, May 31, 1945, Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University.

“Oxnam, Dulles Ask Halt in Bomb Use,” New York Times, August 10, 1945.

William D. Leahy, I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time (New York: Whittlesey House, 1950), 441.

Ibid, 441.

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, “The Atomic Bombs and the Soviet Invasion: What Drove Japan’s Decision to Surrender?,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, www.japanfocus.org/-Tsuyoshi-Hasegawa/2501.

Memorandum for Chief, Strategic Policy Section, S&P Group, Operations Division, War Department General Staff, from Ennis, Subject: Use of Atomic Bomb on Japan, April 30, 1946, “ABC 471.6 Atom (17 August 1945), Sec. 7,” Entry 421, RG 165, National Archives.

This piece seems to be more a selective presentation and interpretation of information than a “debunking.” Importantly, the entire post is based on a single (albeit interesting and thought provoking) book with a specific perspective. Given that the topic discussed is hotly debated, its not clear to me why you leaned so heavily on this single perspective. Regardless, there are several claims in this piece that are misleading. While there may be others I have not addressed here, I believe the four points I discuss are sufficient to add important nuance to the narrative presented here. (Full disclosure: I, like most people, am opposed to the use of nuclear weapons.)

1) "...which is especially relevant at a time when the US government is planning to spend a staggering $1.7 trillion over the next decades to build new nuclear weapons that could endanger the survival of all life on this planet."

This claim is misleading for two reasons. First, the projected spending is $1.7 trillion over THREE decades. The use of "next decades," without specifying how many decades, is not only odd but may give a casual reader the impression that the US is projected to spend $1.7 trillion over the next decade – which would truly be a staggering amount! Admittedly, I had initially read the sentence as “next decade” myself. Second, the spending is for the modernization of nuclear weapons and associated INFRASTRUCTURE. This is important to note, as much of the spending will likely not be spent directly on weapons. It's also important to ask how the nuclear weapons are to be "modernized." For example, is it possible that their blast radius may be reduced to allow for selective, tactical use of these weapons which, while still deadly, would serve to significantly reduce their destructive capacity? This may not be the case, but this is one important question to ask before implying that the purpose of these modernization efforts is to further "endanger the survival of the planet."

2) “First, it is important to contextualize the Japanese situation and mindset in 1945. Japan was facing a hopeless situation in the war. It had lost most of its overseas territories, resources, and allies. It had suffered heavy casualties and damage from conventional bombing raids by the US…Japan was aware of its inevitable defeat, but it was reluctant to accept unconditional surrender, which was demanded by US President Harry Truman, because it feared that it would mean the abolition of its monarchy and the execution of its emperor, whom the Japanese population at the time essentially revered as a god.”

Several inaccuracies and omissions here which are important to consider to fully contextualize Japan’s situation in 1945. First, contrary to the claim made in this paragraph, Japan still had control over most of its imperial territory by August 1945. Large swaths of East and Southeast Asia were still occupied by millions of Japanese troops. Second, how is “conventional bombing raids” defined here? What is “conventional” about carpet bombing a city? Tokyo was essentially wiped off the map in March 1945. By the standards of the time, what makes that “conventional” but not the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which had a much lower immediate death toll than the bombing of Tokyo? If the idea is to judge mid-20th century warfare (which was quite primitive) by 21st century standards, then I would argue neither are conventional nor acceptable. If the idea is to provide context, then this framing is utterly misleading. Third, Japan’s situation was hopeless a long time prior to 1945. By 1944, the United States had established air and naval superiority and Japan was unable to launch any major counter offensives. However, the Japanese were hoping to obtain more favorable peace terms (e.g., maintaining their colonies in Korea and Taiwan, maintaining a military, protecting the military junta) by raising the cost of prolonging the war for the allies through steadfast resistance. It is not true that their only concern was the emperor’s wellbeing throughout 1945 and up to August of that year (though this was a major concern). There was a firm belief among many in the ruling military junta of Japan that the US could still be brought to the negotiating table if the costs of further incursions into Japanese occupied territory or an invasion of the Japanese homelands were raised. In fact, up until the day that Japan ultimately surrendered – a week after two nuclear bombings and the Soviet declaration of war – half of Japan’s ruling military council still refused to surrender (a majority vote was needed) and ultimately the emperor himself had to intervene to break the deadlock (going so far as to take the unprecedented step of addressing the nation himself).

3) The entire section titled: “The US’s Knowledge and Options to End the War without the Bomb”

What is the point of this section? Presidents have many advisors and hear many different perspectives. A set of cherry picked quotes does not imply that Truman had full and complete information to make any decision with absolute certainty. We have the benefit of hindsight and can use our imaginations to consider all sorts of different scenarios at no cost, human or otherwise. But Truman did not have that luxury and he was undoubtedly receiving information pulling in both directions, including death toll estimates should the war continue through the end of 1945. Interestingly, one of the sources you pulled from Stone’s book makes it clear that Truman’s decision was not going to be an easy one: “On July 6, the US military’s intelligence assessment was ‘an entry of the Soviet Union into the war would finally convince the Japanese of the inevitability of complete defeat.’ But it added that ‘the Japanese believe that unconditional surrender would be the equivalent of national extinction.’” Based on this assessment, it's clear that Truman was still getting conflicting information about whether Japan had even accepted that its defeat was inevitable a month before the nuclear bombings. Furthermore, one might interpret this information as implying that even the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan may not force their unconditional surrender because the Japanese may choose to continue fighting to avoid what they would perceive to be “national extinction.”

4) The sections titled: “The Motives Behind the Atomic Bombings” and “The Military and Moral Opposition to the Atomic Bomb by Truman’s Top Commanders”

Again, more selective quoting, with many of these coming after the war had ended and with the benefit of hindsight. Also, it's important to note that Eisenhower and McArthur were both involved in debates about whether to deploy nuclear weapons during the Korean war, and Eisenhower, as president, publicly threatened to use them against the Chinese during that war. Furthermore, quotes in which general’s acknowledge that Japan was essentially defeated aren’t surprising. There was absolutely no doubt among the allies that Japan’s defeat was inevitable by 1945. The important question was WHEN Japan could be made to surrender and at what cost. To put this cost into perspective, in the <30 days of fighting between the Soviet Union and Japan after the former’s declaration of war on the latter in August 1945, nearly 100,000 people were killed or wounded. If the fighting in Manchuria, and the rest of East and Southeast Asia had continued for several more months (including the invasion of the Japanese home islands), many hundreds of thousands more soldiers and civilians would likely have perished. Additionally, millions were already starving within Japan and in its occupied territories, and it's likely that many hundreds of thousands if not millions would have died due to famine if the war would have continued.